Your cart is currently empty!

Blog

AMLO All Along

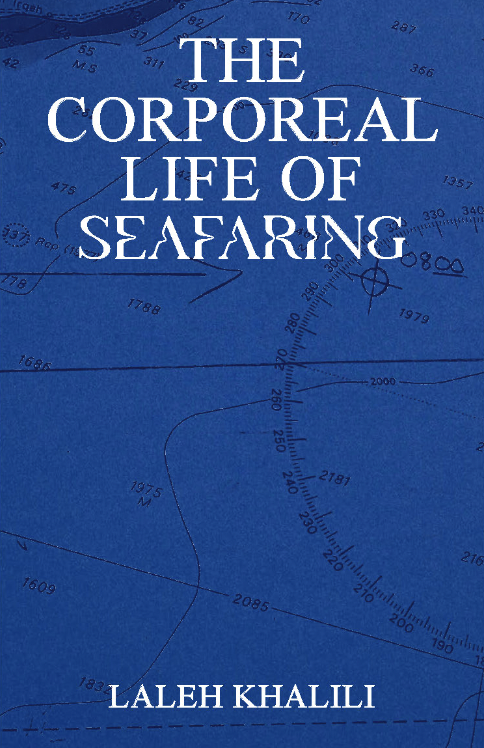

Victor Sebastyen, Lenin, Pantheon 2017, 363. In 1917, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, Lenin was preoccupied with appointing the people that would run… It is difficult to overstate the centrality of shipping to contemporary capitalism. Indeed, without shipping, it is difficult to imagine the birth of capitalism at all. Between 80 and 90% of world trade takes place via shipping, accounting for around 50% of the value of all trade in goods for the European Union and the United States, a figure which rises to 60% for China. Together, these economies account for half of the global GDP. Laleh Khalili, The Corporeal Life of Seafaring. MACK, 2024. 104 pages. But shipping is integral to capitalism beyond its status as the primary mode by which the circulation of goods takes place. Shipping also serves, and has always served, as a testing ground for new methods of worker discipline and exploitation. In this sense, it has long been a harbinger of changes in the global economy—from inaugurating the age of fossil fuel to prefiguring the gig economy to fine-tuning methods of racial hierarchy within the division of labor. Despite this role, life aboard ships has changed remarkably little since the beginning of the European colonization of the world (which was itself only logistically possible due to shipping): racial hierarchies, brutal and hyper-exploitative working conditions, super profits flowing from the periphery to the core. To examine the shipping industry, then, offers a vision of global economic exploitation in miniature, a condensed image of capitalist modernity, of the violence at its origin and the violence required to maintain it. Gulf Studies Scholar Laleh Khalili, who has long been concerned with issues of movement—of people, ideologies, cargo—has recently released a book, The Corporeal Life of Seafaring, which examines the the lives of seafarers and the ways in which they are, sometimes quite literally, shaped by the ships on which they sail. But Khalili’s book—a small, deep-sea blue volume, which, despite its diminutive size, is densely packed with historical, anthropological, and political-economic research—has just as much to say about the global economy that has formed shipping as we know as it does about seafarers themselves. The book draws both from Khalili’s knowledge of the history of and contemporary reality of shipping in the Gulf of Arabia, but it is also, in a way, a work of reportage and field work. In order to write the book, Khalili sailed on the CMA CGM Corte Real and the CMA CGM Callisto, living and eating with their crews. In August, I spoke with Khalili about The Corporeal Life of Seafaring, the centrality of shipping to the global economy, and the ways seafaring life has changed or, just as crucially, remained the same over time. ▼ Jake Romm: I wanted to talk a little bit about logistics studies writ large, because I think that when many people think of logistics studies, they think that it simply means studying the most efficient way to move something from point A to point B. But of course it’s much more than that. And in your writing elsewhere, you talk about the centrality of logistics studies to understanding capitalism as well as the global economy and the geopolitical structure of the world. I was wondering if you could explain what logistics studies actually is, how shipping figures into it, and its importance for our understanding of capitalism. Laleh Khalili: On the question of logistics studies, it’s kind of funny because I’m not necessarily sure that I would consider myself too much of a logistics studies person. The kinds of things that I’m concerned with are not necessarily just the questions of logistics. What I’m interested in more broadly speaking, along with other comrades like Charmaine Chua, Rafeef Ziadah, Deb Cowan, or Martin Danyluk, and a number of other people that I have coauthored with and other colleagues that are working in this area, is the question of, as you say, the centrality of the movement of goods from point A to point B, but not simply this movement of goods, because what logistics entails is the process of acquiring or extracting primary materials. It includes the movement to the production sites, it includes the kinds of politics of movement itself, which necessarily brings not only workplace politics into play, as for example, you see a lot in The Corporeal Life of Seafaring, but also the broader kind of macropolitics that are observed between states and transnationally, and across time as well. And in fact I would say that what perhaps began the field in its critical iteration was Deb Cowan’s extraordinary The Deadly Life of Logistics, which came out in 2014, and which was actually crucial in allowing us to see that the way the simple circulation of cargo throughout the world in order to keep the operation of capital going was also dependent on labor. It was also dependent on war. It was also dependent on a whole series of processes, including managerial softwares, and coercion, custom, and forms of contention that emerged in those settings. And I think we’re all indebted to Deb for that critical queering of the field of logistics studies. But of course, we all went in different directions. So for me, one of the things that was really interesting from the get-go was the fact that a lot of the time when people talk about logistics, unless they’re talking about military logistics, what they often mean is cargo in containerized shipping. A lot of the histories of shipping or a lot of the histories of modern commercial logistics in fact begin with the invention of the standardized container in the 1950s, and then its consolidation and its kind of hegemony from the 1970s and ’80s onwards. What was really interesting to me was that the process of containerization was completely and utterly predicated on a lot of the practices, management styles, and even actually the kinds of softwares that were used, as well as the kinds of processes and the kinds of relationships that were obtained between management and workers that had already been tested out in oil tankers, which had been around since the end of the 19th century, but really the beginning of the 20th century. So still staying big picture—seafarers’ daily bodily life aboard the ship is the main concern of the book. But before getting to the seafarers themselves, I think it’s maybe important to give people a bit more context about the type of industry that shipping is, because it’s really wild. And I think the ownership structures of these ships are just in some sense almost comical in how byzantine they are— Completely sinister actually. Definitely. I think of the Ruby Mar, the ship that the Houthis sank in March. Both the Houthis and the British themselves, I think, believed it to be a UK ship, but only because the Lebanese man who owned the ship had a single residential address in the UK for insurance purposes, a country which the ship otherwise had nothing to do with. I’m not sure that he was Lebanese, actually, I think wasn’t Ruby Mar the one that had an Israeli ship owner who had registered the ship in the Isle of White or the Isle of Man? It was a Lebanese businessman and it was flying under the Belizean flag. But, either way, this is kind of illustrative of the point… It is often quite unclear what the ownership structures are. So to talk a little bit about this: for people that have, for their sins, read Marx’s Capital, logistics really fits in volume two, which is concerned with questions of circulation and the extent to which questions of circulation actually feed into the processes of capital accumulation. So one of the things that makes ownership structures within shipping particularly of interest, not just to people who are ship nerds or maritime nerds, is the fact that in some ways they actually intensify, they embody, they distill the characteristics of capital as it is operating today in its purest form. What does that mean? That means that you have the processes of value extraction and exploitation that we are all familiar with, because of course that is what seafarers do, and of course, that’s what Marx writes about in regard to train workers or train operators in Capital volume two. But there are other legal processes and political layers added to the processes of ownership and exploitation, which make shipping a clusterfuck, technical term. The ways in which it’s a clusterfuck is exactly the ways in which capitalism takes shape in each sector, absorbing the preexisting forms of ownership and preexisting forms of exploitation, incorporates them and builds upon them. Because the residues of previous systems all continue to exist in various forms, depending on the context, in capitalism everywhere. And we see that also in shipping. So one of the things that has characterized shipping for a very long time, is that shipping companies were often used for merchant trade. The people that were involved in the merchant trade had locations all over the world, but often actually kept the ownership structure very strictly within the family itself. So family ownership continued to be, and actually, rather amazingly, still continues to be one of the most significant forms of ownership that exists in shipping throughout the world. And here I’m not just talking about some dude who owns two ships and sends them out. I’m talking about, for example, CMA-CGM, which is the third largest shipping company in the world. I’m talking about Maersk, which is often number one or two in the world. I’m talking about MSC, which is also often number one or two in the world. All of them are based in Europe, and their ownership is entirely held within certain families. So one of the things about this kind of family ownership structure is that it actually completely and totally evades scrutiny. It allows for the shipping company to maintain a large degree of secrecy. The processes of investment into the businesses are done privately or in ways that, again, evade scrutiny. And in some ways, of course, that makes these kind of an ideal form of capitalist corporation because of course that evasion of scrutiny is really central to them. So that’s the first thing. The second thing is that there are processes in which a ship owner, like any other business owner, has to interact with the state or with international legal bodies. That usually happens through the processes of corporate registration. And we know from the experiences of the United States, but also global experiences, that places that tend to be much laxer in terms of their, let’s say, labor regulations, et cetera, but at the same time have very strong enforcement of contracts, tend to be the places where corporations like to register themselves, e.g. Delaware or Panama or the Cayman Islands. Delaware is inshore-offshore, but essentially these places are offshore spaces where scrutiny is evaded, the regulatory processes for registration and other kinds of things are extremely thin, whereas the obligations of the contract are enforced very strongly. And of course that means that it acts to the benefit of the capitalist. Many companies are registered in these places, but some of them are not. So CMA-CGM, for example, which I keep referring back to in part because I think it’s a really interesting instance of these kinds of shipping companies. It’s based in France, but it was set up in the 1970s by Lebanese Syrian exiles from the Civil War in Lebanon. They moved to Marseille, they set up a shipping company to sell cars, kind of dodgy because at the time a lot of cars were being stolen during the Civil War in Lebanon. Nobody knows how or why, never mind, we’re not going to say anything that could get me in trouble. But nevertheless, they started a “roro,” a “roll on

Health Equity Capture

“The Nisha Chicken Salad” on Weight Watchers’s website bears little resemblance to the salad Nisha Godfrey went viral for in 2022. It is two cups… It feels impossible to sit and write amidst the constant grief and urgency demanded in this ongoing genocide. Yet we feel compelled to write—compelled to document and archive the mobilisations that have emerged during this moment, in an effort to inscribe collective memories and pass on the knowledge(s) gained. To account for the successes, failures and learnings that we must carry forth and build on for our next phase of resistance. One emerging tactic has been the disruption of imperial energy circuits feeding the Zionist project. Insurgencies targeting energy have erupted globally, but this article seeks to chronicle a particular disruptive nodal point in Turkey, documenting the tactics used, learnings taken and the investigative research that has informed them. Energy in all its forms – coal, crude oil, jet fuel and natural gas – play an active role in fueling the illegal occupation of historic Palestine. Indeed, the Israeli military cannot run without a steady influx of imported fuels, whether it is crude oil fuelling military tankers, jet fuel powering fighter jets or coal electrifying weapons factories. Energy is inseparable from Israel’s ability to perform genocide. Turkey is the critical conduit and infrastructural node for one of these energy supply chains: Azerbaijani crude oil to Israel. Its Ceyhan port is where oil tankers are loaded and shipped to the Zionist entity, and Turkey also controls the majority of the BTC pipeline which runs through vast swathes of its territory. This crude oil accounts for more than 60% of the Zionist state’s fuel imports, forming a key part of its energy strategy. In 2024, Israel became the preferred destination for Azerbaijani oil, generating over $297million in revenue for the Azeri imperialist regime currently enacting its own genocidal and settler project on Armenian lands. In Israel the use of crude oil is also critical to performing its own genocide, as it is the raw material needed to fuel military tankers and domestically produce jet fuel, the resource that powers the aerial warcraft bombarding Gaza. As such, the explicit violence of crude oil is undeniable as is Turkey’s explicit role in fuelling the flames in Gaza. The transport route of this oil is equally important, as it connects the Palestinian, Armenian and Kurdish struggles through the commodity flows. The oil is supplied from extracted resources in the Caspian sea near the city of Baku—where COP29 will be hosted—travelling via the Baku Tbilisi Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline (partly owned and solely operated by British Petroleum) before finally arriving at the Ceyhan port terminal in Turkey. The majority of the pipeline passes through Turkish territory which in addition to its operation of Ceyhan port, makes Turkish authorities the essential controlling force in the flow of oil to Israel. So, why is Turkey not enacting an oil embargo? Despite several calls to halt the flow of oil by civil society groups, the Turkish regime remains silent. Erdogan’s government has deployed a plethora of performative solidarity acts such restricting jet fuel and steel exports to Israel, but none have halted or decreased the loading of oil tankers bound for Haifa. This is because the BTC pipeline has its own political importance for the region’s imperial powers. In its early construction stages the newly inaugurated Azeri ruler stated he would use the pipeline’s oil revenues to increase military power and threaten ‘war’ with Armenia. A materialised reality we witness today. Similarly, the infrastructure goes through the edges of the Kurdish region occupied by Turkey and, like other state infrastructures, has been used to police and displace Kurdish villages. Indeed, the pipeline is guarded by the notorious Gendarmerie, the military force associated with the displacement, destruction and torture of Kurdish villages and people. As such the flows of oil to Israel through this pipeline are critical to Turkey maintaining its imperial control over these populations and lands, facilitating the use of carceral force to do so through justifications of ‘securing infrastructure’. Turkey, therefore, is clearly unmotivated to stem the flow of oil or the use of this pipeline. As we see, in tracing energy extraction and consumption we are following the entrails of imperialism’s bloody footprints. It is ethnic cleansing, the devastation of traditional societies and incarceration of populations that is the necessary component to exploit natural resources, and it is the use of that resource that powers military genocides in Palestine, Armenia and beyond. In spite of this, insurgent cartographies across time and space have transformed these energy sites into sites of contestation. Through strikes, blockades and protests organised by workers and activists, popular movements have sought to dismantle these flows of energy and their colonial apparatuses, including from within genocidal states like Turkey. During the ongoing genocide in Palestine, one particular group of note has emerged: Filistin İçin Bin Genç (One Thousand Youths for Palestine), coming together to “amplify the voice of the Palestinian intifada” and establish an anti-imperialist front in Turkey that exposes it as a “collaborator sustain(ing) Zionism”. Members of the group tell us that their main objective is to expose Turkish corporations and state apparatuses that “feed Israel” behind closed doors through continued diplomatic and commercial relations. It is an imperative, they add, to “cut all relations with Israel, including…the suspension of oil shipments from Ceyhan Port”, a critical node of complicity that pushed the group to disrupt SOCAR, the Azeri state-owned oil company that is the second-largest shareholder in the BTC pipeline and therefore operates and profits from the extraction and delivery of oil to the Zionist state. Filistin İçin Bin Genç’s insurgencies have provided a map on the breadth of Turkish complicity that also spans beyond this port and pipeline. Indeed their actions on the ground resisted and counteracted the performative solidarity displayed by the Turkish regime, instead organising material support to Palestinians through the disruptions of trade routes and energy circuits. The group began their cartography of insurrection by targeting Zorlu Holdings, a Turkish conglomerate based in Istanbul. The corporation has significant investments in Israeli power plants that generate 1,000MW of electricity annually, amounting to 7% of Israel’s annual needs. Upon uncovering this link, Filistin İçin Bin Genç launched the group and organised their first protests in January 2024 at the company headquarters, calling on the multinational to ‘shut down the plants and cut the electricity’. This was followed by successive protests at shopping malls also owned by Zorlu Holdings, creating new methods to simultaneously target the corporation’s complicity, weaken its public image and increase public awareness on Turkey’s role in fueling the genocide. Quickly the group next targeted İÇDAŞ, revealing another corporate node on the map of Turkish abetment. İÇDAŞ is a Turkish corporation that works in construction, concrete production, energy and mining services – particularly iron and steel. To this day, İÇDAŞ still provides 25% of Israel’s steel, an important material in the literal construction and expansion of the Zionist project – including pipelines. As part of the Independent Industrialists and Businessmen Association (MUSIAD), İÇDAŞ is bound by government decisions, including the trade ban on steel and iron earlier this year imposed by the Ministry of Trade. The continued supply of steel to Israel, despite the ban, further exemplifies the performativity of this legislation and Erdogan’s commitment to his commercial and trade relationship with the Zionist state. In order to expose this, Filistin İçin Bin Genç held a press conference outside the MUSIAD headquarters entitled ‘Cut off Trade instead of Organising Congresses’. This was met with heavy insults and threats from the MUSIAD management who eventually called the Turkish police. Moving towards another site of complicity, Filistin İçin Bin Genç escalated their tactics by targeting a third company, Limak Holding. This corporation is considered within Erdogan’s ‘close circle’, a gang of five corporations who collectively won nearly all large tenders during Erdogan’s time in office. All these companies have differentially supported continued trade with Israel during this genocide, with Limak Holdings specifically providing unfettered use of its port for the daily shipments of crude oil, steel, iron and fuel to Israel. To counter this collusion, Filistin İçin Bin Genç targeted the companies headquarters and galvanised the protestors throughout police violence by delivering a powerful speech that spurred on the collective revolt. Their biggest direct action was yet to come: an occupation of the SOCAR offices in Istanbul. SOCAR is—the fully state-owned national oil and gas company of Azerbaijan—headquartered in Baku (where the BTC pipeline commences) yet holds several offices in Turkey. As the direct link to the corporate-state supplier of crude oil to Israel, and a majority stakeholder in the BTC pipeline, this was the group’s biggest opponent yet. Initially, on April 6th 2024 the youth movement protested on Istiklal Avenue, one of the most famous streets in Istanbul, to publicly amplify their call for the cutting of all commercial and diplomatic ties with Israel. Despite unprecedented police violence—including the torture and detention of several Filistin İçin Bin Genç members who were denied access to lawyers for extended periods—the group continued to protest. Galvanised by their rising public image and appearing on several news channels, members chanted ‘Killer Israel, Erdogan Collaborator’ in Taksim Square on Labour Day and five were arrested. The activists were held in custody for 25 days and questioned about the actions on April 6th in Istiklal Avenue. Regardless, the youth group continued to provide one of a few oppositions to Erodogan’s lacklustre solidarity with Palestine. On May 31st the movement gathered outside SOCAR’s offices, graffitiing the doors before finally occupying the residence for several hours. Described as the ‘peak of their organising’ this target represented the pinnacle of their direct actions, targeting the central figure in Turkish complicity and flows of oil to Israel. But such resistance was suppressed with strong state action. At the time of writing, two Palestinian members of Filistin İçin Bin Genç were incarcerated and at risk of deportation on charges of insulting the President who remained steadfast in his logistical and trade support for the Zionist entity. In response, the group released a fiery statement denouncing these arrests and reiterating “the guilty ones are those who continue to collaborate with the Zionists” and tagging the Ministry of Interior. A wave of solidarity ensued, with both local and global groups staging sit-ins outside Turkish embassies and the Istanbul AKP Provincial headquarters where their Palestinian friends were being held. Coordinating this transnational network of active comradeship put significant pressure on the Turkish regime who finally released the Palestinian activists. At this moment, the group’s actions had not only mapped Turkey’s complicity in genocide but had curated a counter-map of solidarity, counterposing the capitalist networks of violence that bind us with webs of solidarity that resulted in emancipation. The bravery and resilience of Filistin İçin Bin Genç in the face of such violence and personal cost cannot be underestimated. Their commitment to exposing imperial power and raising public awareness is a critical learning for future movements, as well as their acute understanding of how the circulations of energy and capital sustain the settler state. Their singular focus on Palestine allowed the movement to unite groups from across the political spectrum, avoiding classical leftist divisions to ensure an effective and united front in service of liberation. In organising interruptions, a diversity of tactics and targets was likewise essential, generating a multilayered strategy that at once disrupted and exposed the variety of corporate and political actors benefiting from the energy matrix supplying Israel. From the producer of Israeli electricity, to the suppliers of steel, to the shipping companies used to export oil and the corporate operator itself—the totality of the energy circuit was revealed and challenged through their organising. They created not only a counter-map of global solidarity but a counter-map of national resistance to Turkish complicity. Moving forward, other resistance groups must remember the violent realities of energy imperialism beyond Palestine, connecting the Armenian, Kurdish and Palestinian struggles bound by

A Thorn in the Occupier’s Eye

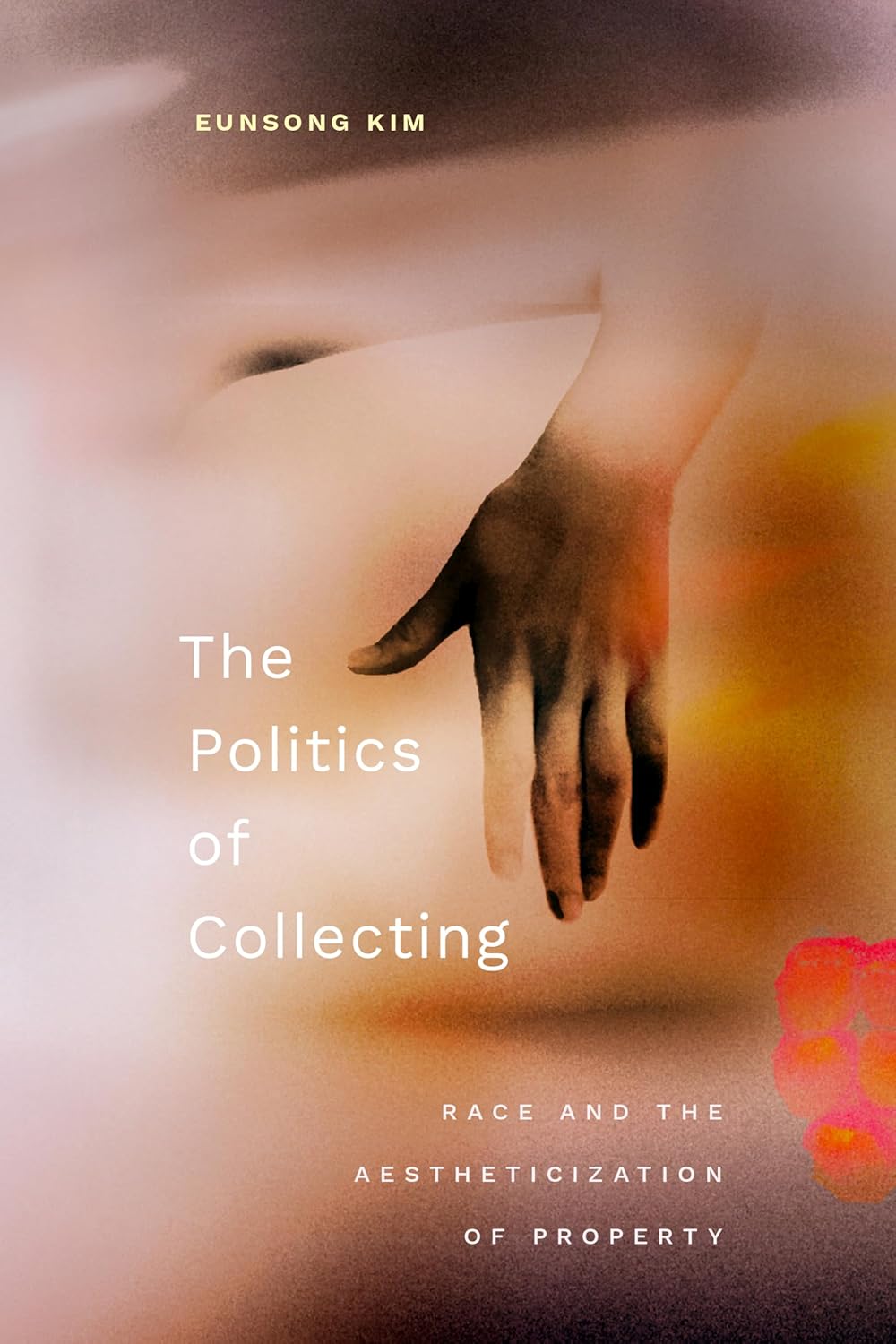

South Lebanon is a lesson in steadfastness — an obstinate and determined testament to the willingness of an indigenous people to confront their occupier and… Eunsong Kim, The Politics of Collecting: Race and the Aestheticization of Property. Duke University Press Books, 2024. 328 pages. Eunsong Kim is a poet, writer, and Associate Professor of English at Northeastern University. Her new book, The Politics of Collecting: Race and the Aestheticization of Property, traces the history of US museums to conceptual artists like Marcel Duchamp to dispel myths around artistic merit, avant garde art, and white male genius. Kim’s research dives deep into primary documents – Jim Crow-era financial statements, correspondence between art curators and financiers, and labor movement records – to ultimately look past much of the romance and mysticism that veils modern and contemporary art to ask questions about the human price of institution-building. The book is essential reading for arts workers who feel conflicted about their desire to support creativity while feeling despair in current systems available to do so. It is an elegy for lives destroyed under false pretenses of charity and aesthetic advancement. It is vindication against recent violences committed by the institution that are mismarketed as caretaking. As Kim dares to put it, “whose garbage becomes the archive?” ▼ How did you look at the history of art and understand all the violence that has made it possible without becoming disillusioned with art making or discrediting aesthetics altogether? I mean, I am fairly disillusioned. I’m excited that the book is able to offer, perhaps, more than my own personal disillusionment. Something that is very clear to me and in researching and writing the book were just very basic questions of like, how much did it cost and how did the institution acquire it? Something that was very much on my mind was going back and thinking about my own education process, like how I learned about certain works of art, how I learned about certain collections of poetry, and how education and institutions were so pivotal to my learning, the learning that I do against the institution or in spite of the institution. When I was at the Getty as a graduate student, I noticed how the Getty would offer these “free” bussing programs, where they would bus in students from all over Los Angeles so they can go through The Getty and learn about art, and then the docents who would be at the site would be volunteers that would take the students through the museum. I think on paper, this sounds like a fantastic program. Why shouldn’t students all over Los Angeles experience looking through the Getty? But if you peel it back, the Getty as an institution collects pre-19th century Western European art. This is the mandate of the founder of the museum. These are the collections that he wanted, and that’s why the photo section is separate from the museum. This is the version of aesthetics that he left for the world, and that continues to be perpetuated because this was his understanding of what is considered important and beautiful. It reifies this argument that I think is naturalized for so many people, that art is an exceptional thing that you do at the benevolence of somebody else. Somebody granted this to you, and you have to go and be really respectful and in reverence of this institution. But these institutions are fundamental sites of expropriation. From when you’re young to when you’re old, they’re always these exceptional spaces. Our definition of art making is constantly removed from this thing called life. At the end of the book, I’m really trying to think about, what else can art and aesthetics and all of these words that are incredibly fetishized be? Is it just this professionalized site that’s the place of the institution, or is it something that is part of our lives? I’m interested in the inspirations you take from your religious upbringing – as you say in the opening chapter that accepting the good will of wealthy Christians meant “enforced gratitude.” I wrote that at the very end. It just was like me sitting with, “What is my relationship to like the collection?” What’s my relationship to the Arensberg Collection and the Philadelphia Art Museum? On one level, it’s hilarious to me that I’m looking through all of their sales books. Something that I don’t think it was imagined that this is why the sales books were acquired – for a researcher like me to look through and think about labor history, or the history of racial capitalism and the development of their collections. But this motivation is personal in some ways, because I think I see this logic of benevolence in so many arenas, and I want to just help undo some of the the guilt and anxiety that I think that accrues in a lot of spaces that if one is paid or one receives an award, then one does not a critique institution. I agree with you that I always feel like artists can be more critical; that they should take initiative to say “no” to things that are unethical. But sometimes I wonder how much individual agency we really have. I mean, you know, I read Lucy Lippard. I’m here to bite the hand. And yet, I see people like David Velasco getting fired from ArtForum just for publishing a letter in support of Palestine or Samia Halaby losing an exhibition over similar remarks. There are serious repercussions for saying anything. In the first chapter, when I’m going through the paintings that Henry Clay Frick purchased, I do not think that the political impetus is on the artist, the way that I think a lot of debates end up concentrating on like, is the artist in the show? Is the artist not in the show? Did the artist say yes? Did the artist say no? I actually think it feels like the worst kind of individual liberal thinking, because I do think that, in fixating on the individual artist, what gets missed is the entire history of the structure of the institution. We bypass what the roots really are like, what the power structures in place are doing, because we’re fixated on the “good” artists or the “bad” artists. And I think even if we have our fan favorites, which I do, that conversation makes it so that even if you get one board member off, how do they get appointed? What’s that process? When I was in the Frick Collection, the one thing that was so clear to me was that someone needs to write a book on the history of board formations. How was this decided that all of these institutions just have boards? And I can say that for some of the earlier museum boards, it’s not like there was an artist, but if there is, there’s one or two. Board members are mostly other billionaires. They’re mostly other corporate executives, so they’re all run like corporations. With the board members of the Frick, like Rockefeller and Mellon, how did all of these people who profess that they don’t know anything about art become the board of this museum? They’re prioritizing financial immortality. I think a bigger question is, what if some people have more agency than others? What’s the conversation going to look like when everyone has equal access to this thing called agency? Why do some people have more agency in an institution to do certain things, to fire people for signing letters? I think rather than fixate on what does it mean for someone to say yes or no, the question should be flipped and say, why is it that some people can fire other people? Well, I fixate on people. What I appreciate most about the book is that it helps me think through more recent conflicts I fixate on, like Dana Schutz’s abstraction of Emmett Till. It was a section, but I took it out. I realized that there’s actually been so much good writing on it that I don’t need to say something. But obviously, that’s another really good example. People really tried to die on that hill, you know, in defense of her. And it was shocking. Do you think your analysis of Santiago Sierra’s neoliberal aesthetics can apply to that instance, not only to the physical depiction, but the fact that curators couldn’t entertain the destruction of an artwork? I am always really curious about this conversation on destruction of our objects. In an earlier essay, I write about how the former CEO of the Getty says something like, “we take refugees, why can’t we take their objects?” Mostafa Heddaya wrote a while ago about how so many museums freaked out when they thought objects were being destroyed in Iraq by various different militant groups. And then it turned out like those were all fakes, but the museum curators and CEOs, without making a statement about the war, would immediately make a statement about the objects, without even verifying whether or not the objects in the museum in Iraq have been destroyed. I think you see a lot of these moments where there seems to be an impulse to buy a Western Imperial understanding of the world that you save the objects, but when we’re thinking of care for people, communities and the environment, that seems separate. Which is truly wild, right? There is something that is happening collectively that protection of the object seems to supersede protection of the people. This is to say, I don’t think that all objects should be destroyed. I think that’s a fun position. But when does someone get to say these objects are no longer part of us? I found the fundamental celebration of destruction of objects as manifestos that were written by Surrealists and the futurists that are celebrated in art history as part of this art. If it’s done as performance, and there’s documentation of it, that seems okay, because it’s continuing a line. But when the object becomes something that people get to decide on because it’s part of their lives, that’s where the conflict seems to be. I want to stay on this issue and consider if prioritizing a “debate” or “conversation” over actual actionable change might also be part of neoliberal aesthetics. In your discussion of Louis Agassiz’s daguerrotypes of enslaved people at Harvard, there also seems to be a lot of time and resources wasted on debating whether or not objects that perpetuate anti-black violence should remain under white ownership and circulate casually for public access – something that should not even be up for debate. Yes. One of the main questions is, if Harvard can take care of it in a way that the descendant cannot. If it is in her care, what if they fade? What if they’re damaged, and then what if they dissolve? They did fade under Harvard’s care. Very few people talk about the fact that they also didn’t fully take care of it. And then they digitized it, and so now, it’s theirs forever. But they were objects that were created to support a white supremacist understanding of the world. If the descendants decide that they are going to do something else with it, how many people get to partake in that conversation? It’s not even conceivable that images that were made essentially to uphold enslavement, we can’t imagine destroying that. Fundamental preservation is not the objective. [The descendants of who were depicted in the daguerrotypes] don’t get to decide, in any way, shape or form, how it exists in their lives. It’s decided for them and on their behalf. I want to talk about Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) and what he called “readymades” – all of which you have chosen not to reproduce photographs of in this book. I just figured that, like I didn’t reproduce any of Santiago Sierra’s work, he himself has talked about how

Announcing the 15 Winners of the Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards 2024

I want to thank everyone who submitted to The Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards. We had many amazing entries, and I’m always astounded by the myriad of ways photographers tell… The post Announcing the 15 Winners of the Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards 2024 appeared first on Feature Shoot. I want to thank everyone who submitted to The Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards. We had many amazing entries, and I’m always astounded by the myriad of ways photographers tell stories with such creativity and diverse perspectives. While each project stands on its own with unique themes, together, they emphasize our shared struggles, triumphs, and connections. From issues of displacement and illness to the search for identity, this year’s winning photographers present relatable stories that emphasize our interconnectedness. We are excited to announce that the following photographers will be showing their projects at Clamp Gallery in Chelsea, NY, on August 30, 2024. You can RSVP here for free. Congratulations to: ©Jonathan Jasberg Jonathan Jasberg – “Cairo: A Beautiful Thing Is Never Perfect” “The title of the project borrows from an ancient Egyptian proverb: ‘A Beautiful Thing Is Never Perfect.’ With these candid photographs that are far from perfect—sometimes messy, grainy, and rushed—through the spontaneity of a mix of classic and contemporary candid photography styles, I aim to show moments of joy, sadness, quirkiness, and hope. To not only show a glimpse of the complexity of Cairo and the lives of the people who live there but also include moments that, even if we come from a completely different background, we can relate to, smile at, empathize with, and appreciate the shared beauty and complexity of life. “A beautiful thing is never perfect.” —Jonathan Jasberg Ariana Gomez – ”My Mother Speaks of Land as Memory” “My mother speaks of plants. To her, we are created with roots that snake down into the deep, dark earth inserting themselves like veins into our hearts, into our souls. For her, this is truly home, a soul home. And hers has never been Texas. You see, she was uprooted. Her soul home is Puerto Rico, the place she only remembers as a small child when everything is towering, and colors are the most vivid. Her roots tore as she boarded a plane at eight years old, never to return. She speaks of unlived lives in the lush watery world where she last thrived.” —Ariana Gomez Chinky Shukla – “When Buddha stopped smiling” Cattle Yard, Pokhran, 2022 ©Chinky Shukla “Tucked away in a scorching side of Pokhran, a township in the north-western province of Rajasthan in India, is an ugly story of a nation’s atomic might. In the summer of 1974 on Buddha’s birth anniversary, India blasted its way into the world’s consciousness by testing a nuclear device. It was heard, but in that loud rumble of earth, triggered by a series of nuclear explosions, generations lost their voice. The desert dwellers of Pokhran are still paying the price of India’s nuclear story that unfolded in the sand dunes nearby.” —Chinky Shukla This work is supported by the National Geographic Explorer grant. Yusuf Eminoglu – “The Aquatic Ceremony” The Aquatic Ceremony I ©Yusuf Eminoglu “In the harsh winters of Güroymak/Bitlis/Türkiye, the local children have turned the cold January days into a ritual of their own, finding warmth and joy in the natural thermal waters. As they bathe their horses and buffaloes, the striking contrast between the freezing air and the soothing warmth creates moments of playful delight. For these children, this place is more than just a washing spot; it becomes a stage filled with fun and exuberance. “This photo series offers a glimpse into a lifestyle that thrives outside the bounds of the modern world, rooted deeply in the heart of nature. It captures how the children and their animals embrace the opportunities provided by the natural thermal springs. Each photograph tells a story of resilience and community, where the simplicity of their ritual holds a deeper meaning.” —Yusuf Eminoglu Natalia Kondratenko – “On the other side” ©Natalia Kondratenko “On this stage, there are no actors. My imagination comes forward into the light. Everything that I cannot express in the real world. Why? Because freedom is needed, but it remains only in my imagination.” —Natalia Kondratenko NC Hernández – “No Se Vende” Manu Sol Mateo ©NC Hernández These photos explore the world of underground, female, and gay cabaret singers and burlesque performers in Mexico City, set against the backdrop of an abandoned 19th-century mansion in the Centro Historico. The juxtaposition of subaltern realities and decaying Victorian sensibilities invites the viewer to ponder notions of otherness and opulence, and the beauty of the absurd. The subjects are both underground cult figures in Mexico City and famous not only for their songs and performance but also for their elaborate stage costumes that explore themes of transgressive sexualities, internalized colonialism, and traditional Mexican art.—NC Hernández Naohiro Maeda – “You must believe in spring” You must believe in spring #01 ©Naohiro Maeda “This project is about exploring my unreliable narrative as an immigrant, as someone alien to a new territory. My work integrates photography and embroidery, creating unique pieces that deconstruct and reconstruct landscape imagery. I capture photos during car journeys, often with my partner driving. I then digitally manipulate these raw images, employing excessive image correction tools(“retouch” and “blend” functions) until they lose their single vanishing point. “Once the digital manipulation is complete, I print the images on matte photo paper and begin an intricate process of hand embroidery. This step involves making hundreds of white knots on the inkjet print surface, a technique inspired by Sashiko, a traditional Japanese embroidery method used to mend and reinforce garments.” —Naohiro Maeda Antonio Denti – “Notes From the Edge. Vol. 1” Notes from the Edge of the Economy. (Catania, Italy) ©Antonio Denti “’Notes from the Edge’ is a photographic exploration of the incredible times we are living. Times when the old world seems to have ended, but the new world doesn’t seem to be here yet. Times of transition, turmoil, unknown. Times of excitement and terror, forward leaps, and violent recoils. This strong tide – which seems very difficult to control and also even to understand – involves human lives at multiple levels, from macro to micro: history, economy, climate, inner feelings, and human connections. “’Notes from the Edge’ tries to catch a glimpse of it at as many different levels and in different situations as possible. The constant element is a feeling that human lives have been put to the edges of what we were used to by fierce and momentous developments.” —Antonio Denti Ludwig Nikulski – Pod Palmami – Under the Palm Trees Construction site of a church. Pervomaisc, Transnistria, February 2023. // People say that more churches are being built in Transnistria to distract the population from the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. ©Ludwig Nikulski “Palm trees – most people associate them with the South Seas, vacations and relaxation. Where no one would expect to find the tropical tree: Along the Ukrainian border. The work POD PALMAMI – UNDER THE PALM TREES explores the question of how the presence of the Russian war of aggression is tangible in its absence. In Ukraine‘s neighboring countries, the war is closer than ever. And yet it remains mostly invisible. “This project is a visualization of Ukraine‘s western external borders and a photographic document of a changing area – the geographical line that currently separates Europe from the war. The photographs were taken between 2022 and 2024 with an analog large-format camera in Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Moldova, the Russian separatist state of Transnistria, and the autonomous region of Gagauzia. “While the war in Ukraine rages in the background of this work, I was always also looking for other realities happening at the same time. The plastic palm trees on the military outpost of a vacation village in Poland; a beautifully dressed woman in a Romanian Orthodox monastery next to a vacuum cleaner; a broken-down car drowning in the floodwaters at a diner in Slovakia as if it were sleeping in the Mississippi; the song Life is Life playing on the radio while bushes scrape the outside of our car as the driver dodges potholes at high speed on the road to Odessa; or simply the beautiful landscape of a riverbank in the dim morning light in Moldova that is forbidden to photograph. This work is my note of that time.” —Ludwig Nikulski Gleb Simonov – “Coronal” ©Gleb Simonov “The American myth of the dark forest is largely an inherited European narrative, formed in a different age, culture, and, most importantly, a different ecosystem. Yet this myth is still projected onto the modern young, often unsustainable monoculture forests that are largely the results of reforestation, their histories openly visible in the land: one can identify plow terraces, lack of pillows and deadfall, uneven numbers of older and younger trees — all pointing either to agriculture, pasture land, or clear cuts. What, then, is a ‘true’ forest? “Old Growth is a series of fragments of late seral forests in virgin, disturbed, and modified states. In equal measure, it focuses on ecosystems and infrastructure — trails, elevated platforms, service roads, signage, remnants of past use — all the different levels of intervention created to manage the forest and accommodate the visitors. It is also, to some degree, a study of sacred groves and the similarities between protected forest land and traditional temples — explored in a separate series of poems, still somewhat of a work in progress.” —Gleb Simonov Jordan Tiberio – “You Have Touched Me, and I Have Grown” Jordan Tiberio “You Have Touched Me, and I Have Grown” is an unreleased project created in August 2022 at a residency in the French village of Orquevaux. It is a visual love letter to womanhood that explores the transformative value of relationships between women, how these bonds shape our personal growth, and how they encourage bodily autonomy. “During the creation of the work, I was grappling with the suffocating weight of a toxic, five-year relationship, whose codependent orbit I felt powerlessly trapped within. The residency granted me respite from this dynamic, immersing me in a centuries-old, idyllic village in the company of 16 strangers– all women– from various walks of life. While listening to my peers share stories of their own experiences, I came to understand that independence was not a daunting prospect but a liberating path forward.” —Jordan Tiberio Maria Oliveira – “Bone Foam” ©Maria Oliveira “There is a pagan and earthly dimension that hovers over all things and cannot be ignored. The earth is touched by the whole body. By invoking my ancestry, familial, physical, and spiritual – the place from where we start – I understand that the cycles get closer, and they flow naturally. The transient movement can be magical and mysterious. The feminine presence is constant and intense. Women generate, create, kill and feed. The bodies of the things and the people are not forgotten. They find a place to land and remain there, ajar in time. “Between connection and encounter, I recognize that we are a part of the larger scale of things, where what we know and what we don’t know fit. It seems to me that we are not exceptional. Everything that exists part from us and is part of us.” — Maria Oliveira Patricia Fortlage – “Lemonade – The Duality that is Chronic Disease” Resilience ©Patricia Fortlage “This is my story about life with chronic disease and disability. I would like it to serve as a love letter to the chronic illness community… especially the women who are most gaslighted by medical professionals and others in our communities at large. This is a photographic fine art series with careful attention to raising women up in the process. You see, I, myself, have a life-threatening illness. It is called Myasthenia Gravis, and it has thrown me into the deep end of what life is like

‘Take One a Day’ Exhibition Raises Suicide Awareness in Rural UK County

Trigger warning: Mention of suicide Paul Gutherson, a Lincolnshire, UK resident, was out walking his dog one day when he found a suicide victim. Deeply traumatized by this event, he… The post ‘Take One a Day’ Exhibition Raises Suicide Awareness in Rural UK County appeared first on Feature Shoot. ©Richard Ansett Trigger warning: Mention of suicide Paul Gutherson, a Lincolnshire, UK resident, was out walking his dog one day when he found a suicide victim. Deeply traumatized by this event, he sought therapy and later started taking photos of his natural environment. One a day. A chance discovery of these photos on Facebook by an old friend Jason Baron—former Head of Creative Photography at the BBC—led to the creation of the “Take One a Day” photo exhibition. Currently on view at Lincoln’s Usher Gallery (through September 15, 2024), the exhibition, curated by Baron, highlights a deeply personal and community-focused initiative around this sensitive topic, bringing the darkness into light, and bringing the local community together through art and discourse. The photographs are all taken in Lincolnshire, a region with one of the highest suicide rates in the UK and one with significant mental health challenges, especially in its large farming community. The show features amateur photographer Paul Gutherson’s daily landscape photos alongside large-scale portraits of “mental health advocates and other people suffering from mental health challenges” by photographer Richard Ansett, as well as contributions from various local artists inspired by the project. This project included engaging local groups like Men’s Shed and Bro Pro, who shared their stories and participated in the exhibition. This initiative aims not only to honor the memory of those lost but also to foster dialogue and support within the community. We spoke with Baron to learn more about putting together this important show. If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or a crisis, please reach out immediately for help. Here is a list of international suicide hotlines. ©Paul Gutherson How did you become involved with this project?‘Three years ago I kept seeing an old friend of mine, Paul Gutherson, posting a landscape photo a day on Facebook with no caption. I recognised the place as it was across the canal from my old house where I used to hang out with him when we were kids. We both grew up in a rural market town in the east midlands of England. ‘Paul is an amateur photographer and the pictures were just shot on iPhone but therewas an odd quality to them I found interesting. I contacted him and he told me thestory of how he came to ‘Take One a Day‘ in the place he did. ‘He was walking the dog one morning when he came across a bag on a bridge, looked around to see if anyone was there but no sign. Twenty minutes later he came back and found someone who’d died of suicide in the same place. Deeply traumatised he sought help and during therapy for PTSD he realised he needed to reclaim the positive feelings hehad about the place he loved walking the dog in and that had been part of his life fordecades. He decided to go there everyday and try and find something beautiful totake a picture of. ‘Instead of ‘taking one a day’ of his prescribed Diazepam. It could be a flower, a sunrise, a big sky, his dog on the path etc. These are the pictures I saw and wanted to tell their story. ‘I’d curated a show for the BBC a year or so before and loved doing it. I knew this would be an interesting and potentially important project. And one which may in the end give meaning to the poor person who felt they couldn’t go on and who took their own life. In October 2023, I managed to get private funding to put on a show at Spout Yard Park, a small gallery in Louth, a town close to the landscapes, for World Mental Health Day 2023. Off the back of the success of that show we were offered two enormous rooms to fill with content at the prestigious Usher Gallery at Lincoln Museum (on view through September 15, 2024).’ ©Paul Gutherson How does this exhibition aim to contribute to conversations around suicideprevention and mental health awareness?‘Off the back of Paul’s photos, and the idea of a mental health awareness photography exhibition, photographic artist Richard Ansett, who I’d worked with on many assignments, kindly offered to explore the themes through portraiture. He’s a Samaritan volunteer and we’d done lots of mental health documentary shoots together for the BBC. ‘He took a trip to Lincolnshire and the place where Paul took the photos, contacting local Samaritan groups and others to get willing subjects. He came across two groups, Mens Shed and Bro Pro, and uncovered stories of people with their own mental health difficulties who were willing to tell them and have their photos taken. We found brilliant stories and lovely people, from mental health practitioners and Samaritan volunteers, to people really struggling mentally. ‘Off the back of visiting the space many people have been moved to reach out to friends and relations and the groups involved to seek help.’ ©Richard Ansett What is it about this particular land/area made it the right fit for exploring thetopic of suicide?‘Lincolnshire has a large farming community with issues of rural isolation, and suiciderates there are very high. It’s a relatively deprived area in many districts and menthere are not known for being open with their emotions and feelings. Interestingly wehope that is changing, and from the initial Bro Pro group David Bruce set up a fewyears ago, there are now over ten groups across the County with men meetingweekly to chat and help each other peer to peer.’ So many people have written abouthow they’ve been inspired by the project, and we know people have been jolted intogetting in touch for help off the back of it, which is amazing.Jason Baron, CURATOR What were some of the most significant challenges in curating this exhibition, particularly given its sensitive subject matter?‘With obvious sensitive themes we were in contact with the local police about the suicide. Bizarrely it turned out that one of the police force there was a friend and carer of the deceased. He was fully behind the project so long as they remained anonymous. ‘Family members were informed about the project for both the smallexhibition in Louth and then the larger one in Lincoln. We know they have visited andlove the fact that we’re bringing some meaning to the person and are providing apositive space for people to think about their own stories. We had strong Samaritan backing and they even ran an outreach session being present in the gallery for a whole day during the run.’ ©Richard Ansett What role do you see art and creativity playing in the healing process forindividuals affected by trauma or loss?‘It’s all there in the comments book of the exhibition really. So many comments abouthow searching for beauty and creativity in the everyday can heal. It’s a familiartheme we don’t pretend to have invented, but with Paul being disciplined enough toget out everyday and actively seek out something to take a picture of it’s an obviousexpression of art therapy. It’s transformed him.’ We hope people see from all the aspects of the project that there is power in community and connecting with the natural world and each other.Jason Baron, CURATOR How do you hope this exhibition will impact the local community and thosewho visit it?‘We’ve read the comments book, we’ve seen and shown the art inspired by theproject, and worked with local groups who’ve been so supportive of what we’redoing. People have reached out for help directly off the back of the exhibition. Weinvited a local mindfulness practitioner, Amanda at Unique Yoga and Meditation inLincoln, to run sessions in the space based on the themes. The response wastremendous. Richard Ansett took on a residency near the start of the show inLincoln, part of which saw him take on a street photography experiment in Lincolnwhich we hope will form part of a future exhibition.’ If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or a crisis, please reach out immediately for help. Here is a list of international suicide hotlines. The post ‘Take One a Day’ Exhibition Raises Suicide Awareness in Rural UK County appeared first on Feature Shoot.

A Day in the Life of Gregory Crewdson

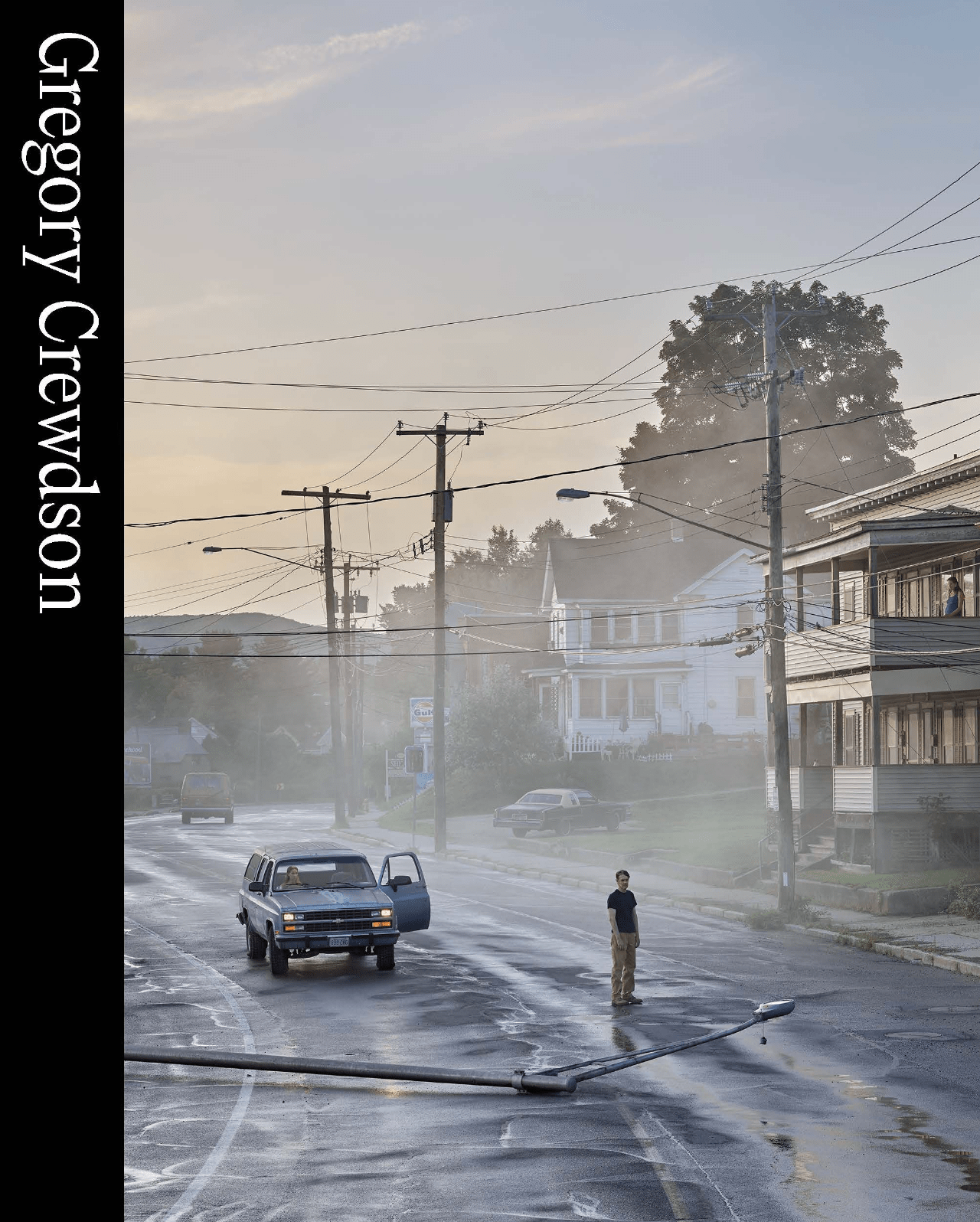

Gregory Crewdson’s new “retrospective catalog,” Gregory Crewdson (published by Prestel and edited by Walter Moser), is a spellbinding journey from start to finish. As someone who grew up in the… The post A Day in the Life of Gregory Crewdson appeared first on Feature Shoot. Gregory Crewdson by Walter Moser © 2024 The Albertina Museum, Vienna, and Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York Gregory Crewdson’s new “retrospective catalog,” Gregory Crewdson (published by Prestel and edited by Walter Moser), is a spellbinding journey from start to finish. As someone who grew up in the 1980s, encountering his earliest work—which he made as a student at Yale (where he is now a professor and director of Graduate Studies in Photography)—was quite a visceral experience for me. Gregory Crewdson, Untitled. From the series: Early Work, 1986-1988. Digital pigment print.The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, Permanent loan –Private Collection © Gregory Crewdson The interiors from this series are like stepping into a time capsule, evoking memories of playdates at friends’ houses and visits with older relatives—spaces (and times) long forgotten. Just as in his later work, I find myself taking in the atmosphere and paying close attention to the details. The sense of place is powerful: one can almost hear the TV static and smell the stale cigarette smoke in the air. This early work, laced with mystery and unease, sets the stage for viewing the rest of the book. Seeing the evolution of his style and subject matter laid out and printed over the nine chronological series feels gratifying- like putting together a puzzle. Inspired by Edward Hopper, David Lynch, Walker Evans, and Raymond Carver, the layers are many. Gregory Crewdson, Untitled (Sunday Roast), From the series: Beneath the Roses, 2003-2008. Digital pigment print. The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, Permanent loan – Private Collection © Gregory Crewdson In preparation for my interview with Crewdson, I read almost all of his interviews (as you do). It turns out that there are a lot of interviews with Gregory Crewdson, so I decided to focus on his daily life. Here’s a snapshot. Gregory Crewdson ©Harper Glantz Morning Routine Gregory Crewdson’s day begins around 7:30 a.m. in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where he lives with his partner and writer/collaborator, Juliane Hiam. After spending many years in New York City (he grew up in Brooklyn), Crewdson moved to this small town in 2010, settling into a converted church next to his studio, formerly a firehouse. His mornings are centered around open-water swimming, a routine he admits is time-consuming but a non-negotiable part of his day. Before that, he drinks a cappuccino and discusses the day’s priorities with Hiam. Currently, it’s just the two of them running the show, and they are organizing the next production. A1 Conditions. 07/29/2024 ©Gregory Crewdson The Daily Swim Open-water swimming (in the summer months) is integral to Crewdson’s routine. He admits that a part of his personality is obsessive and addictive, so he thrives on structure and builds his day around this activity. He also finds swimming to be a vital part of his creative process. The time spent in the water offers him space for reflection and allows thoughts and images to surface. Crewdson takes his daily swim in a nearby lake, accessible only by a 20-minute hike through the Appalachian Trail. Despite the sometimes chilly and rainy conditions, he swims the length of the lake daily, which takes him about an hour and 20 minutes. “There is something about the isolation,” he tells me. “Photographers, in general, have a slight separation from the world, and not to romanticize it, but it is a time to reflect.” Although the outdoor swimming season in Great Barrington is fleeting (he swims in indoor pools in the off-season and does cross-country skiing in the winter months), he values being “one with nature” and emptying out his thoughts. Even when traveling, swimming remains something he can’t live without. Gregory Crewdson, on the set of Cathedral of the Pines with Director of Photography Richard Sands. 2013. Courtesy Crewdson Studio Production Crewdson divides his life between pre-production (which can last many months), production, and post-production. Being in production takes the least amount of his time, but it’s his favorite part of the process. He admits to being “jealous of artists who can go in their studio every day and make work,” but this is the only way he knows how to make his pictures. Right now, however, he’s in the pre-production phase, and a big part of his day is spent location scouting for the next group of pictures he’s currently working on. He describes his location-scouting process as the only time he’s alone and a “very old school process.” He’s tried hiring location scouts and looking online, but driving around is still the only way that works for him. Scouting, an “elusive process,” takes him months of “driving in what seems like circles” until something strikes him, and he can imagine what could happen there. Listening to Audible keeps him company (he’s currently re-listening to Richard Ford’s “Independence Day”). “Location scouting is filled with possibilities. Nothing is ruined yet,” he tells me, “and that changes as you become restricted by budget, circumstance, or failure.” Crewdson tends to shoot for six weeks, and he has a line producer and Hiam (who also produces). “No matter how you cut it, he says, “the budget is always around the same amount of money, and it’s never easy. “A day is like a movie, and it’s very expensive. There is a lot of pressure to get as many pictures as you can get done over this period of time.” Wind down Crewdson tells me he’s incredibly inspired by movies. As the day winds down, or if he’s feeling blocked creatively, he’ll watch a movie or TV show. Mad Men remains his favorite series (and he’s watched it repeatedly with Hiam), but he confesses to liking both “Top Chef” and “Alone”, which he watches “unironically.” Gregory Crewdson (Prestel, August 25, 2024) is the groundbreaking artist’s first career retrospective, produced to accompany a major exhibition at the Albertina Museum in Vienna. You can follow his studio news and swimming adventures on Instagram. The post A Day in the Life of Gregory Crewdson appeared first on Feature Shoot.

Cuba’s Underground: Diversity, Art, and Rebellion

Shibari, tattoos, and drag queens are not the first things to come to mind when one thinks of Cuba. However, photographer Jean-François Bouchard shows us that there is an underground… The post Cuba’s Underground: Diversity, Art, and Rebellion appeared first on Feature Shoot. Felix Gonzales Martinez & Katherine Carmona. Havana, Cuba . Fall 2021 Shibari, tattoos, and drag queens are not the first things to come to mind when one thinks of Cuba. However, photographer Jean-François Bouchard shows us that there is an underground in Cuba that is diverse, creative, and highly aesthetic. Bouchard has been photographing hidden Cuba since 2016 and is releasing his book The New Cubans on November 7, 2024, at Paris Photo. How did you first encounter this “lesser-known Cuba” shaped by nonconformity, creativity, and diversity? “In 2016, a friend introduced me to a young actor who was very involved with the LGBTQI+ community. And he said, “Come see another side of Cuba that you might not have seen.” He then took me to a drag queen bar which was everything you would expect from such a venue…Except that it was owned by the government (like pretty much else in Cuba). This fascinated me because I had read about the shocking concentration camps in which the very same government was incarcerating gay men in the ‘60s. How do you go from operating gay prisons to owning a drag queen bar?” Felix Roman with Ehliani de la Carida Vazquez Hernandez. Havana, Cuba Spring 2017 How long have you been working on this series? “The first images were shot in 2016 but I only kept one for the book. “I only really started in 2021 when I connected with Devon Ruiz on Instagram. She is a young, dynamic, creative woman with iconoclastic looks—she has more than twenty tattoos on her shaved head—and an attitude to match. She was dabbling in photography, painting, dance, modeling, and fashion while seemingly being the queen of Havana nights. We hit it off immediately and she became my key to a Cuba that not many foreigners get to see: a spectrum of young people from various alternative lifestyles to the blossoming LGBTQI+ community. She was my entry point into a Cuban parallel world that foreigners know little about, much less get invited into.” How did you gain access to the intimate and often private spaces of these young Cubans? “Devon was my key to the city. Very rapidly it expanded to her group of friends who all became involved in one way or another. “One night, I followed her to visit her friend Osmel Azcuy who was filming a music video in a very traditional house with its maximalist, frozen-in-time Cuban decor. The house was filled with young, tattoo-covered people who looked like they had been plucked out of Los Angeles, Berlin, or Tokyo. The contrast was striking between “traditional Cuba” and “new, young Cuba.” The clash was so powerful that it created a surreal, almost cinematic experience for me. I wanted to capture that feeling and made my first images there. For the first time in over twenty-five years, I felt that I got something new in the photographs.” Many of your subjects have left or plan to leave Cuba. Why is this, and how do you see this culture evolving? “Just as I started the project, the situation deteriorated in Cuba and migration shot through the roof. This was mainly due to the tattered economy providing limited prospects within the country. But in my opinion, this is just part of the story. What compounds the dissatisfaction and the urge to leave is the simultaneous exposure to what is happening elsewhere in the world via the Internet and social media. The contrast is shocking to many Cubans. “Consequently, migration is now at an all-time high, surpassing the great migration crises of the ‘80s and ‘90s combined. It is estimated that 2% of Cubans leave the country each year. That’s 200,000 people! Some leave by plane with proper visas but others embark on dangerous journeys that claim lives. “Early on in this project, it became obvious that a large portion of my subjects would be leaving the country before I could complete it. I became aware that many of my images would act as mementos of dissolving groups of friends and of lives left behind. It made my work more emotional than what I am used to.” Manuel Salgado Sanchez Idarra, Kenia Bakle Bucles, Luis Alejandro Saldivar Salinas. Havana, Cuba How did the recent widespread access to the Internet in Cuba impact the youth culture you documented? “During my visits prior to starting this project, I was witnessing the early impacts of Internet access and the influx of Americans to the island (which only lasted a few years under Obama). But Internet access was still a very cumbersome affair consisting of sluggish, public Wi-Fi access points in parks where groups of people would assemble with computers and phones. It was bizarre. “Many also subscribed to the “El Paquete,” a black-market distribution of memory sticks with bootleg copies of the week’s most popular YouTube videos, Hollywood movies, and Netflix shows. One gig of global culture for two dollars a week! “But in 2019, it really exploded when Cubans gained access to the internet on mobile phones. Suddenly, the world entered the lives of young Cubans.” What was the most surprising or unexpected aspect of Cuba’s youth culture that you encountered during this project? “I was really surprised to sometimes feel like I could be with young folks from Tokyo, Los Angeles or Berlin. In a matter of just a few years, their influences became global. But at the same time, they have a rich and unique Cuban culture that still instills a local flavor to their world.” Victor Alfredo Hernandez Garcia, Adriana Perez Dominguez. Havana, Cuba In what ways has the Cuban art community responded to your work? “Enthusiastically. Many of my subjects became collaborators and brought their friends to participate in the project. A Havana-based gallery will exhibit these works in the spring of 2025.” How do you think the subjects you’ve photographed see their role in reshaping the perception of Cuba on a global scale? “They are tired of many perceptions or clichés about Cuba. They want to be perceived as people who are also part of global culture and contribute to it.” What do you hope audiences will take away from The New Cubans?“My work is always about celebrating differences and stearing clear of biases. I hope people will discover a Cuba that tourists are not exposed to. I hope viewers will get that amidst the countless hardships of life in Cuba and despite the present-day migration crisis, the younger generation is shaping a new reality defined by nonconformity, gender diversity, and resilient creative expression.” You can preorder The New Cubans here. The post Cuba’s Underground: Diversity, Art, and Rebellion appeared first on Feature Shoot.

From Diagnosis to Healing: Turning a Cancer Journey Into a Powerful Visual Story